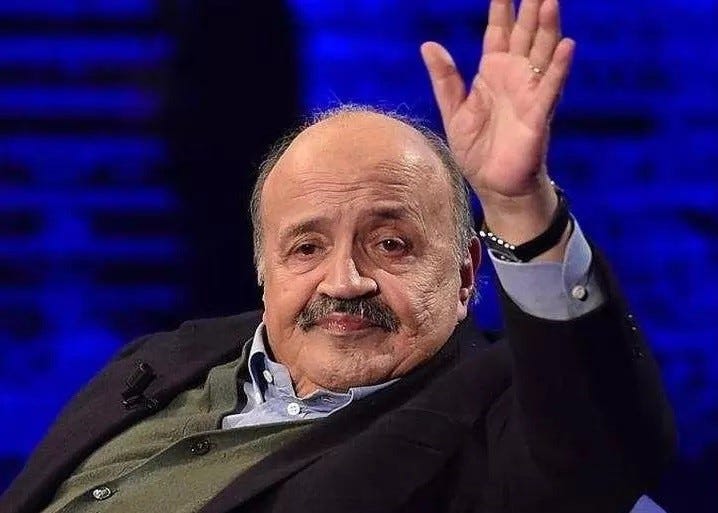

Maurizio Costanzo was a turtle guy.

He admired them for their survival skills and unpretentious appearance. And like people who take on the physical characteristics of their pet, Constanza bore an undeniable resemblance: a balding head protruding from hunched shoulders, the jowly face atop a rotund body. Think Cecil Turtle with a Magnum PI mustache.

Eventually, he collected thousands of small ceramic turtle figurines from fans and friends. In return, he often gave them to guests who appeared on his television show, which turned out to be quite a lot of people. Over 40,000 actually.

Admittedly, the turtle is an oddly reclusive animal to match with such a relentlessly public figure. Costanzo lived his whole adult life in the limelight, starting as a journalist in Rome when he was 17, and ultimately as the host of the country’s longest running TV talk show. “The Maurizio Costanzo Show” ran from 1982 until 2022, more than 4400 episodes. In the meantime, there were books, films, theatre productions, marriages (four), romances (more than four), personal scandals and talent discoveries that ranged from comedians and cabaret performers to artists and scholars. All born of an irrepressible energy far more hare than tortoise.

Strangely, what interested me initially in Costanzo was not his TV presence, but rather his association with one of Italy’s most indelible songs of the Sixties: “Se telefonando”, which he wrote with Ghigo De Chiara and the legendary composer Ennio Morricone. It wasn’t a name I expected to pop up in those circles. It would be like discovering that Regis Philbin co-wrote “Good Vibrations” with Brian Wilson.

According to legend, Costanzo and De Chiara, a playwright, had written lyrics for the theme song to Costanzo’s upcoming television show “Aria condizionata”, and met with the maestro Morricone and Italy’s original bad-girl pop star, Mina, in a rehearsal room on Via Teulada in Rome. Morricone had only a microcosm of a musical theme: three notes that he’d gleaned from the siren of a Marseille police car. The recording that emerged is an Italian classic—-Bacharach-style melodies and trumpet lines running smack into a Phil Spector style Wall of Sound. Mina’s high-drama vocal captures all the youthful impulsiveness and budding confidence of a nation shaking off the ashes of the Second World War.

It turns out that Costanzo’s contribution to “Se telefonando” was probably minimal— as little as changing one or two words to avoid the wrath of the Italian censors. Then again, side-stepping the censors was no small matter. Three years earlier, Mina’s affair with married actor Corrado Pani and her subsequent pregnancy resulted in her being banned from national TV and radio. If nothing else, Costanzo’s one foray into songwriting is a testament to his Zelig-like ability to turn up anywhere history was being made.

Ten years later, Costanzo had a hand in another Italian masterpiece, sharing screenplay credit for Ettore Scola’s Academy Award-nominated film “Una Giornata Particolare (A Special Day)’ starring Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni. We watched it recently— it’s a haunting look at a decidedly unromantic one day affair between two Roman neighbors on the day of Hitler’s first visit to the Italian capitol. The film doesn’t flinch from exploring the dark convergence of personal and political complicity in the rise of Facism, and the suffocating strictures around gender roles and sexual identity.

Those subjects would surface on “The Maurizio Costanzo Show” as well, mixed freely with gossip, humor and plenty of argument. “Talk is life” was the underlying principle of the program, and Costanzo hosted politicians, intellectuals, entertainers, and even the drag queen Platinette.

Like an Italian dinner party after dessert is served, the topics were free-ranging and sometimes controversial. In 1991, he broadcast a series of episodes taking on the Sicilian mafia, even burning a “Mafia: Made In Italy” t-shirt on the air. The turtle sticks his neck out.

Two years later, Costanzo and his wife, Maria De Filippi were leaving the Parioli theatre in Rome after filming his show. As their car pulled out, a Fiat Uno parked nearby and packed with 70 kilos of explosives blew up.

Perhaps saved by his ceramic good-luck charms, Costanzo and his wife escaped unharmed. He lived the rest of his life under police protection, which probably proved far more exhausting to the police than to him. He continued his frenetic pace, going right back on the air, writing books and articles, and teaching journalism at two Italian universities for another 31 years.

Maurizio Costanzo died in February of this year. Writing “Se telefonando” for Mina with Morricone, making movies with Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni, hanging out with Prime Ministers and stars like Totò and Alberto Sordi, even being the target of a Mafia hit— it’s hard to imagine a life lived more Italian than Costanzo’s. It ended with an operatic send off in Rome’s Piazza del Popolo.

Much has been written lately of the effects of the “grey wave” in Italy— the challenges of an aging population and the loss that inevitably accompanies it. But the story is about more than demographic numbers. It’s a curtain dropping slowly on an extraordinary cast of characters.

Thankfully, Mina is still here and singing in full voice. At age 83, she just released a song with the young Italian pop star Blanco. But Morricone is gone now, as are film figures like Sordi and Scola. Ground-breaking artists like Mariuccia Mandelli, the “godmother of Italian fashion”, architect Ettore Sottsass, and designer Piero Fornasetti have also been lost. This “boom” generation inherited a country in ruins and in less than 30 years would reimagine it as the land of dolce vita, defining our contemporary conception of Italy with their fierce energy and creativity.

And in the case of Maurizio Costanzo, with a bit of luck and courage as well.