All the time I was in Modena, I couldn’t help thinking about my father.

Not that my father had ever been to Modena— a city in Italy’s Emilia Romagna region that is the birthplace of both balsamic vinegar and the legendary Luciano Pavarotti. My dad was not an opera buff. Nor was he particularly discerning when it came to salad condiments.

But if he didn’t know much about arias or acetos, he did know about automobiles. And when it comes to cars, Modena is at the center of a particularly bright and shiny universe. Chances are if it’s cool, fast and Italian, it comes out of Emilia Romagna, from a 300km stretch known as Motor Valley, encompassing Modena, Maranello, Bologna, and Imola, home of the iconic race track that hosts a Formula 1 Grand Prix.

It was a few years after my dad passed that I made it to Modena for the first time. To be honest, I was drawn more by the promise of tortellini and a tour of the home of the world’s greatest tenor than by a compelling interest in cars. I hadn’t owned one since high school, and living in Manhattan for 30 years had pretty much eroded what little West Coast fascination I had in my youth for chrome and a custom paint job. Much to my father’s chagrin, I never even learned to drive a stick shift.

So why was I standing in Modena’s evening mist outside of a barn filled with motor vehicles, wishing more than ever in my life that I could call my dad?

As an American, it’s a little surprising to learn that automobiles were not invented in the United States. The names behind the invention of the auto are almost as familiar as Henry Ford’s, but decidedly more European. Karl Benz is widely considered the originator in 1886, while Gottlieb Daimler is credited with creating the gasoline engine that made it all possible. Emile Roger from France was one of the first producers. By the time Henry Ford fired up his Quadricycle, the French, Germans, British and of course Italians were already racing ahead.

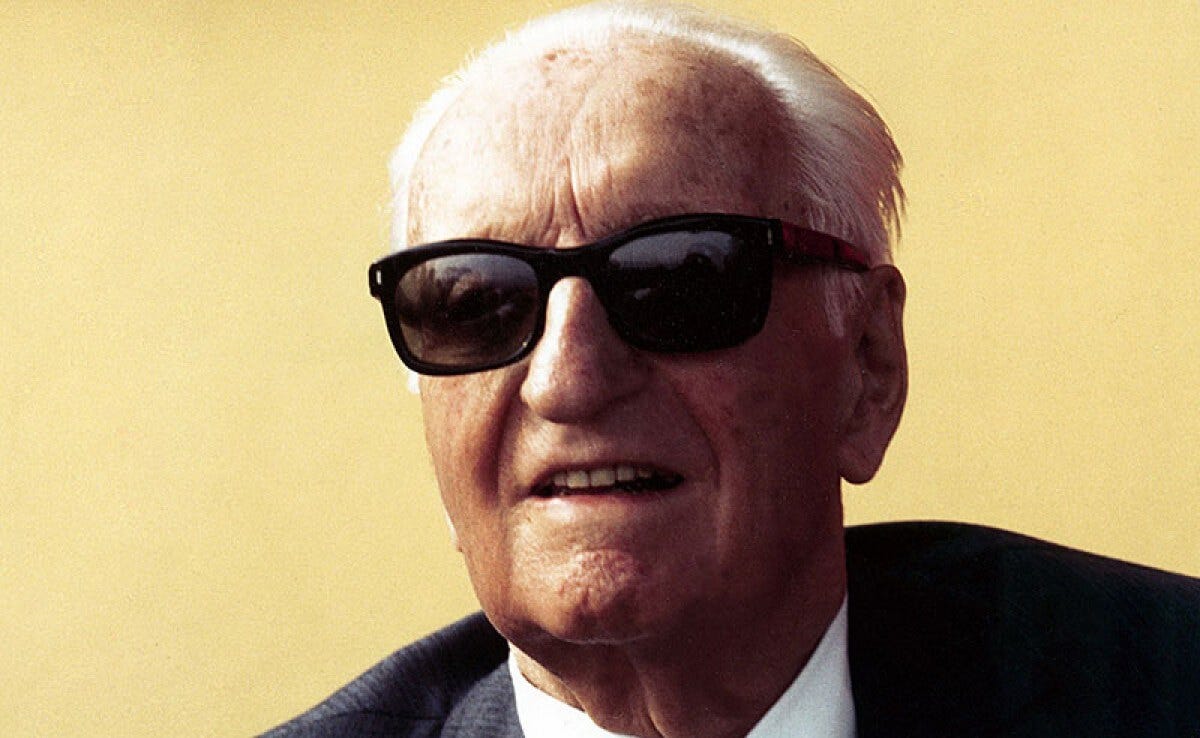

Yea— racing. Human nature being what it is, only a few years after someone first drove around the block, the game of “mine is faster than yours” began. By 1908, the year of Ford’s invention, a 10 year old Enzo Ferrari was watching from the side of the road when the Circuito di Bologna rattled through his town of Modena. Nine years later, Enzo himself was a driver, racing for Alfa Romeo.

The history of Motor Valley is inseparable from Enzo Ferrari, who would go on to turn his father’s metal fabrication shop in Modena into an early workshop for creating his own cars. Although he moved the factory to nearby Maranello to avoid the Allied bombing raids of WWII, his energy and competitive drive drew the best and brightest in the auto industry to the region over the course of the next fifty years: Ducati, Maserati, Dallara.

Perhaps most famously, Ferruccio Lamborghini, whose Modena company produced farm tractors, purchased a Ferrari in 1958 and was disappointed to find that the clutch kept breaking. One day he approached Enzo himself about the problem. Il Commendatore (The Commander), as Enzo was known, suggested that Ferruccio stick to making tractors, and let Ferrari build the cars. Soon Lamborghini was in the auto business as well, going bumper to bumper with Ferrari. Italian guys are like that.

After more than 100 years of churning out some of the world’s most coveted cars, Modena today is not only a factory town but an archive of auto history— home to two Ferrari Museums, one dedicated to Enzo himself and one in Maranello that is linked directly to the manufacturing plant. Both museums are as sleek and polished as the cars themselves, more Miami Vice than Modena grease monkey.

I managed to see both of them during my short visit and still grab a late lunch outside of Modena’s Duomo in Piazza Grande. When I saw the drizzle picking up as I paid my bill, I decided it was an opportune moment to make one last stop on the auto museum circuit. After all, you can’t spend all your time in a Ferrari.

You reach the Maserati Umberto Panini Collection from the agricultural heartland of Emilia Romagna, the green flatlands that grace the world with Prosciutto di Parma and Parmigiano Reggiano. Passing through the quiet plains, the roads narrow until they finally turn to gravel. Pretty soon you have to pull off into the grass to allow approaching traffic to pass. It’s a long way from Maranello’s churning industrial sprawl.

As I approached the museum on a long path lined with poplars, I was starting to worry that my nav system was leading me into someone’s country villa. Then I rounded a corner and saw a cow poking his head through a steel sign that said “Hombre”. Now it seemed pretty clear. Searching for sports cars, I’d somehow driven straight into someone’s farm.

A series of warehouses and animal sheds lined the fields in front of me. Though it seemed an unlikely spot to see even one Maserati, much less a collection, I parked the car and wandered down the muddy road looking for something more exotic than farm animals.

Only when I saw a row of antique tractors with logos like Fiat and Lamborghini lined up outside the last warehouse did I realize that I might be in the right place after all. [Note to file: in the unlikely event that someone offers to buy you a Lamborghini, be very specific.] The lights were on in the building, so I opened the door.

As a boy, I remember going to car shows with my dad—walking into a white-walled exhibition hall and suddenly being thrust into a freeway full of turbo-charged shapes and colors. That rush of wonder came back to me when I stepped into this plain outbuilding in the Italian countryside and plunged into a time machine, packed with more than 60 different models of cars, motorcycles, bikes and yes, tractors, from the early 1900s through today.

Of course there are plenty of Maseratis, but the museum covers far more ground than that. Umberto Panini already owned a substantial collection of classic cars and motorcycles when he bought the Maserati collection, which was being sold off by the De Tomaso company after it acquired the Trident in the mid-Seventies. As the entrepreneur behind the sticker books beloved by young Italian football fans and the proprietor of Hombre farms, one of Italy’s premier biological producers of parmigiano cheese, Panini stepped in to keep the cars in Motor Valley. Luckily he had a barn big enough to park them all.

All I could think was that my father would have loved the place. Not just the cars, but also the improbable location and the unpretentious atmosphere. Maserati initially started as a garage for car repairs, and there’s a whiff of that in the museum. There are tin trays under the World War I motorcycles to catch leaking oil; racing trophies on the window sill; framed prints of car advertisements on the walls. There’s no ticket desk or gift store, just a cluttered corner office where the boss waves you in. Admission is free.

The whole thing takes you back to a time when cars were more about style than money; when the world was excited to be going places and machines symbolized our future rather than our demise. It makes you miss when automobiles were a shared language between different generations, and guys washed their cars by hand just because they liked to.

It makes you miss your dad.

This comment means so much-- really glad the piece connected with you. It's very funny-- I feel like our generation was the one in which the shared language of cars, boats, motorcycles, plumbing, etc. between fathers and sons started to break down. My dad and I could talk about cars and things together and go look at them, but God knows we couldn't work on them together. I have to watch a YouTube tutorial to put chains on my tires. I totally agree with you-- would love to have just some basic skills in the things that Dads used to specialize in. Really appreciate you reaching out. Good luck with that lawnmower.

A beautiful, emotional piece. I’m curious about the Panini museum—when I search that exact name I find a sleek-looking museum that charges admission. Can you tell me how to find the one you wrote about? I’m sure my sons would like to go. Thanks!