It’s ironic. But Valentine’s Day is a hard holiday to love.

Between its religious origins and the Hallmark commercialism of our modern version, this holiday is a mess of contradictions. Is it a tribute to a Christian martyr or an overpriced date night? And what are we celebrating anyway? Like a scruffy, awkward teenager all dressed up for prom, it doesn’t quite know who it is.

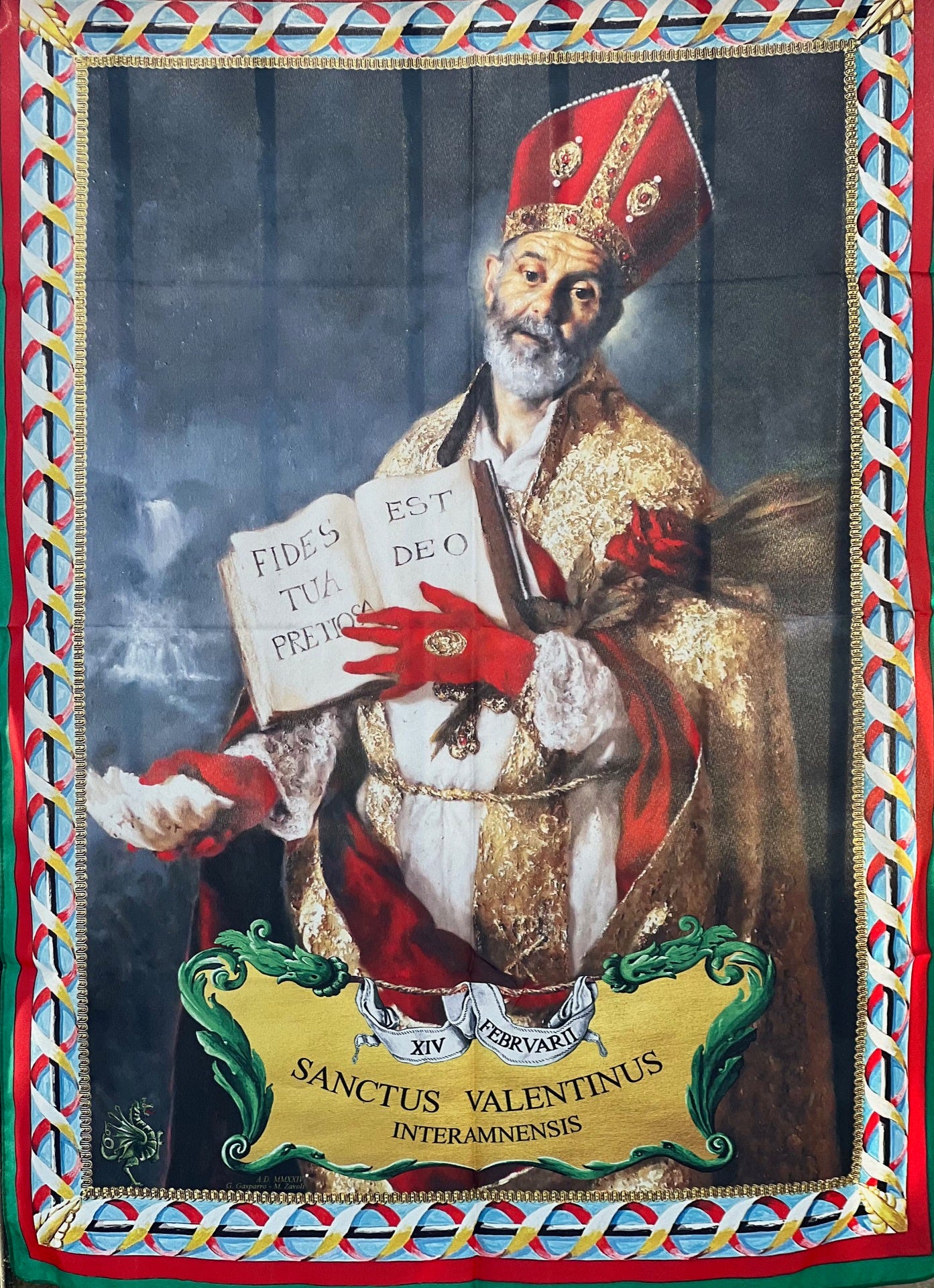

So maybe it’s appropriate that the Saint Valentine for whom the holiday is named is a bit of a question mark as well. In fact, he may have actually been two different people. Or maybe three. He is believed to have lived in the third century. Although some current scholars say it was the fourth. You see what I mean.

Indeed, the story of Saint Valentine is a dizzying combination of mistaken identities, reckless embellishment, morbid suffering, and well-intentioned falsehoods. No wonder he’s the patron saint of love, right?

The one thing we can agree on: there was a Christian clergyman named Valentine who was beheaded by the Roman Emperor Claudius III on the Via Flaminia in Rome sometime around the third or fourth century. Unfortunately, that wasn’t particularly unique. There were three saints named Valentine at that time— two of them working in or around Rome and both may have met similar ends at the hand of Claudius. No wonder there’s been some confusion.

It does appear though that the Saint Valentine we’re looking for came from Terni, a town in the Italian region of Umbria. He was a proselytizer, known for trying to sway young men away from the Roman gods and convert them to the then outlawed Christian faith. When he was arrested and taken to Rome, he even tried to win over the emperor himself, which clearly didn’t go well.

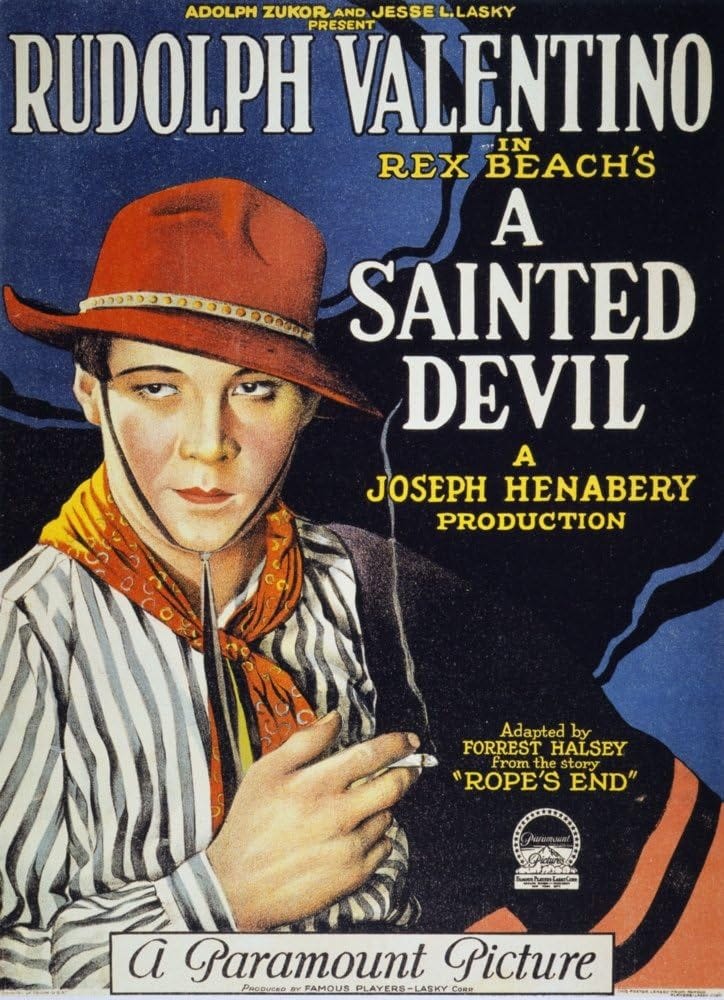

The problem is: there’s no solid evidence that this Valentine ever did or said anything all that romantic or Valentine-like. As it relates to our current perception of the holiday, they probably would have been better off naming it after Rudolf Valentino, the Italian actor whose Latin lover schtick inflamed the movie screens of the 1920’s in gems like “The Sheik” and “Passion’s Playground”.

Not that there aren’t Valentine stories out there. It’s just that many only surfaced long after the saint’s death, and again, it’s not even clear if they’re talking about the same Valentine. The most these tales can offer is a little backstory to support our contemporary Valentine’s Day traditions.

Many of the legends around Saint Valentine recount his penchant for performing secret Christian marriages (which had the added benefit of allowing the groom to escape Roman military service). After performing the ceremony, some say it was the saint’s custom to cut parchment paper into the shape of a heart to remind the men of their vows. Grade school teachers everywhere picked up on that one and ran with it.

Another legend holds that Saint Valentine had a beautiful garden and would give roses to young members of his congregation. When one young couple who received the roses fell in love, more came to be similarly blessed. Soon he had to devote one specific day to blessing marriages. This particular legend is brought to you by Teleflora.

Where all that falls a bit short as an explanation of origin, an alternate theory holds that Valentine’s Day was derived from the Ancient Roman festival Lupercalia, also held in mid-February. In what sounds like the ancient world’s version of a spring break stunt, this was a time when young Roman men would skin a sacrificial goat to make loincloths, then run nearly naked through the streets. Young women would vie to be touched by their shaggy thongs, believing that the contact would aid in pregnancy, which I suppose it probably did.

When the Christian popes gained authority they quickly replaced that festival with one dedicated to the sober story of Saint Valentine. To the surprise of no one, the new feast day proved less popular than the hedonistic bacchanal that preceded it. The Christians finally compromised by making the Valentine feast a celebration of “love” rather than “lust”. I suppose it’s a short road from there to little candy hearts with sayings on them.

But if Saint Valentine’s contribution to what we know as Valentine’s Day can be a little hard to locate, the man himself is quite easy to find. Maybe too easy. After his death, the saint’s body seems to have travelled more than it ever did during his life. A church in Dublin claims to exhibit his heart, while in Glasgow a friary holds his skeleton. In Prague, they have his shoulder bone and Madrid claims to have remains as well. It’s probably a good thing there were two of him.

Yet Italy remains his most recognized resting place. At Rome’s Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin, his skull is on display in a glass box, crowned with flowers. About an hour away, his effigy lies below the altar of the Basilica di San Valentino in his hometown of Terni, in a church constructed on the site of his tomb.

When I visited the Basilica of Santa Maria di Cosmedin last week, I couldn’t help but note that Saint Valentine finds himself a victim of the Roman Empire yet again. There were crowds lined up outside the church, but in a cruel twist, everyone was there to take a photo with the Bocca della Verità, an ancient Roman sewer cover immortalized in the film “Roman Holiday”. Meanwhile, the small clusters of visitors inside the basilica hardly noticed the tiny brown skull that looks out over the shadowy, frescoed, eighth century church.

At least in Terni, the patron saint gets center stage, especially in February. On the Sunday before Valentine’s Day, engaged couples from all over the world attend a Mass at the Basilica di San Valentino, exchanging their vows in front of his tomb. As part of a month-long calendar of events, Terni also hosts the National Chocolate Festival and the Festival Dell’Amore, which includes lectures, concerts, DJ sets, trekking excursions and yoga.

So even here the celebration of Saint Valentine is an awkward mix of the secular and sacred. In the church parking lot, the trees are decorated with red hearts; a tinsel L-O-V-E sign hangs outside the entrance. The basilica itself is located on the outskirts of Terni between a soccer field and a university dormitory, and it might be one of the least romantic churches in Italy. Not that it’s an unattractive place. But there’s no mystery, no lingering scent of incense, no candlelit corners. Visitors seeking more than an Instagram moment are probably looking for love in the wrong place.

Still, it was a spring-like day along the Corso Tacito, so I sat outside and enjoyed a plate of ciriole alla ternana, the local pasta specialty. As the sun rolled slowly across the green Umbrian hills in the distance, I wondered what Saint Valentine might have made of the holiday that bears his name.

Driving home that evening, “Sowing the Seeds of Love” by the Eighties Brit band Tears for Fears came on the radio (that happens in Italy), and I thought of Saint Valentine. Whatever truth there is in the legends, it does seem that his life was spent finding ways to spread the only thing there’s just too little of. To that end, I decided he’d probably be fine with some glittery “love” signs or a stuffed bear holding a cardboard heart.

After all, Valentine also happens to be the patron saint of fainting, epilepsy, and beekeeping. But no one gets a holiday for those things. For better or worse—as he himself might have put it at one of his illicit wedding ceremonies—his legacy is a reminder that love lies at the center of our lives.

So whether the seeds are cliche-ridden cards from CVS, hothouse roses, or boxes of chocolates, I think he would suggest we plant them and see what grows. In these dark months of winter, there are certainly worse things we could be sowing.

Another great post from you! The best part of going to see the “real” (or at least whole) Saint Valentine in Terni is driving around the Umbrian countryside afterwards.

I loved this article. I laughed out loud more than once. Shared it with friends. I agree that it should be published somewhere with a wider reach. Perfecto!! "Be Mine"